| 失效链接处理 |

|

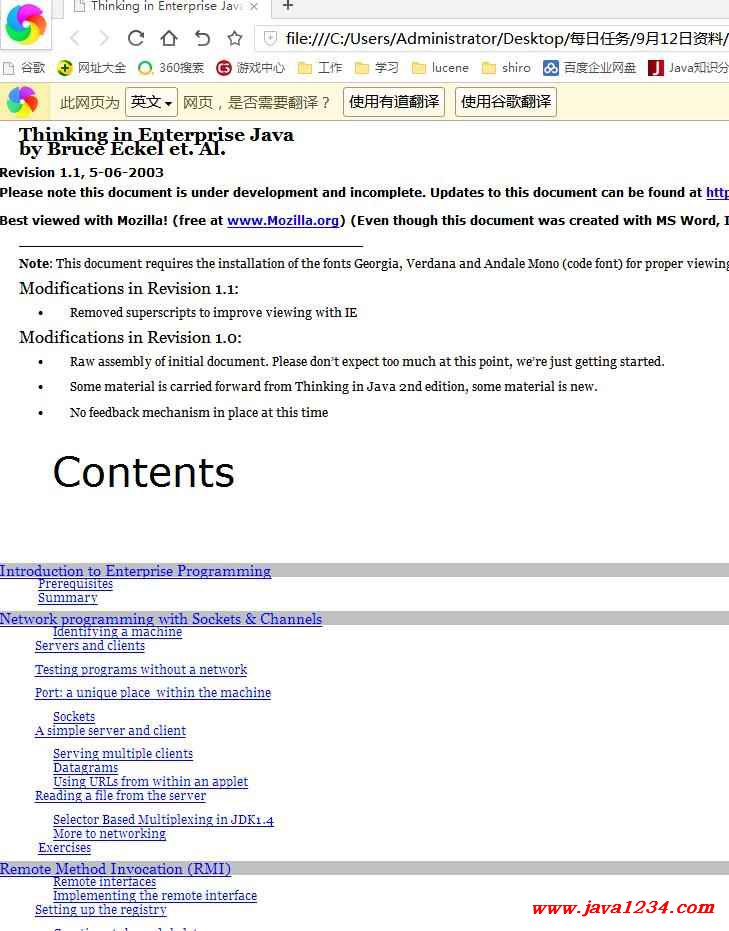

JAVA编程思想(企业版) PDF 下载

本站整理下载:

提取码:txdm

相关截图:

主要内容:

Introduction to Enterprise Programming

Historically, programming across multiple machines has been error-prone, difficult, and complex.

The programmer had to know many details about the network and sometimes even the hardware. You usually needed to understand the various “layers” of the networking protocol, and there were a lot of different functions in each different networking library concerned with connecting, packing, and unpacking blocks of information; shipping those blocks back and forth; and handshaking. It was a daunting task.

However, the basic idea of distributed computing is not so difficult, and is abstracted very nicely in the Java libraries. You want to:

· Get some information from that machine over there and move it to this machine here, or vice versa. This is accomplished with basic network programming.

· Connect to a database, which may live across a network. This is accomplished with Java DataBase Connectivity (JDBC), which is an abstraction away from the messy, platform-specific details of SQL (the structured query language used for most database transactions).

· Provide services via a Web server. This is accomplished with Java’s servlets and JavaServer Pages (JSPs).

· Execute methods on Java objects that live on remote machines transparently, as if those objects were resident on local machines. This is accomplished with Java’s Remote Method Invocation (RMI).

· Use code written in other languages, running on other architectures. This is accomplished using the Extensible Markup Language (XML), which is directly supported by Java.

· Isolate business logic from connectivity issues, especially connections with databases including transaction management and security. This is accomplished using Enterprise JavaBeans (EJBs). EJBs are not actually a distributed architecture, but the resulting applications are usually used in a networked client-server system.

· Easily, dynamically, add and remove devices from a network representing a local system. This is accomplished with Java’s Jini.

Please note that each subject is voluminous and by itself the subject of entire books, so this book is only meant to familiarize you with the topics, not make you an expert (however, you can go a long way with the information presented here).

Prerequisites

This book assumes you have read (and understood most of) Thinking in Java, 3rd Edition (Prentice-Hall, 2003, available for download at www.MindView.net).

Summary

This chapter has introduced some, but not all, of the components that Sun refers to as J2EE: the Java 2 Enterprise Edition. The goal of J2EE is to create a set of tools that allows the Java developer to build server-based applications more quickly than before, and in a platform-independent way. It’s not only difficult and time-consuming to build such applications, but it’s especially hard to build them so that they can be easily ported to other platforms, and also to keep the business logic separated from the underlying details of the implementation. J2EE provides a framework to assist in creating server-based applications; these applications are in demand now, and that demand appears to be increasing.

Network programming with Sockets & Channels

One of Java’s great strengths is painless networking. The Java network library designers have made it quite similar to reading and writing files, except that the “file” exists on a remote machine and the remote machine can decide exactly what it wants to do about the information you’re requesting or sending. As much as possible, the underlying details of networking have been abstracted away and taken care of within the JVM and local machine installation of Java. The programming model you use is that of a file; in fact, you actually wrap the network connection (a “socket”) with stream objects, so you end up using the same method calls as you do with all other streams. In addition, Java’s built-in multithreading is exceptionally handy when dealing with another networking issue: handling multiple connections at once.

This section introduces Java’s networking support using easy-to-understand examples.

Identifying a machine

Of course, in order to tell one machine from another and to make sure that you are connected with a particular machine, there must be some way of uniquely identifying machines on a network. Early networks were satisfied to provide unique names for machines within the local network. However, Java works within the Internet, which requires a way to uniquely identify a machine from all the others in the world. This is accomplished with the IP (Internet Protocol) address which can exist in two forms“:

1. The familiar DNS (Domain Name System) form. My domain name is bruceeckel.com, and if I have a computer called Opus in my domain, its domain name would be Opus.bruceeckel.com. This is exactly the kind of name that you use when you send email to people, and is often incorporated into a World Wide Web address.

2. Alternatively, you can use the dotted quad” form, which is four numbers separated by dots, such as 123.255.28.120.

In both cases, the IP address is represented internally as a 32-bit number[1] (so each of the quad numbers cannot exceed 255), and you can get a special Java object to represent this number from either of the forms above by using the static InetAddress.getByName( ) method that’s in java.net. The result is an object of type InetAddress that you can use to build a “socket,” as you will see later.

As a simple example of using InetAddress.getByName( ), consider what happens if you have a dial-up Internet service provider (ISP). Each time you dial up, you are assigned a temporary IP address. But while you’re connected, your IP address has the same validity as any other IP address on the Internet. If someone connects to your machine using your IP address then they can connect to a Web server or FTP server that you have running on your machine. Of course, they need to know your IP address, and since a new one is assigned each time you dial up, how can you find out what it is?

The following program uses InetAddress.getByName( ) to produce your IP address. To use it, you must know the name of your computer. On Windows 95/98, go to “Settings,” “Control Panel,” “Network,” and then select the “Identification” tab. “Computer name” is the name to put on the command line.

//: c15:WhoAmI.java

// Finds out your network address when

// you're connected to the Internet.

// {RunByHand} Must be connected to the Internet

// {Args: www.google.com}

import java.net.*;

public class WhoAmI {

public static void main(String[] args)

throws Exception {

if(args.length != 1) {

System.err.println(

"Usage: WhoAmI MachineName");

System.exit(1);

}

InetAddress a =

InetAddress.getByName(args[0]);

System.out.println(a);

}

} ///:~

In this case, the machine is called “peppy.” So, once I’ve connected to my ISP I run the program:

java WhoAmI peppy

I get back a message like this (of course, the address is different each time):

peppy/199.190.87.75

If I tell my friend this address and I have a Web server running on my computer, he can connect to it by going to the URL http://199.190.87.75 (only as long as I continue to stay connected during that session). This can sometimes be a handy way to distribute information to someone else, or to test out a Web site configuration before posting it to a “real” server.

Servers and clients

The whole point of a network is to allow two machines to connect and talk to each other. Once the two machines have found each other they can have a nice, two-way conversation. But how do they find each other? It’s like getting lost in an amusement park: one machine has to stay in one place and listen while the other machine says, “Hey, where are you?”

The machine that “stays in one place” is called the server, and the one that seeks is called the client. This distinction is important only while the client is trying to connect to the server. Once they’ve connected, it becomes a two-way communication process and it doesn’t matter anymore that one happened to take the role of server and the other happened to take the role of the client.

So the job of the server is to listen for a connection, and that’s performed by the special server object that you create. The job of the client is to try to make a connection to a server, and this is performed by the special client object you create. Once the connection is made, you’ll see that at both server and client ends, the connection is magically turned into an I/O stream object, and from then on you can treat the connection as if you were reading from and writing to a file. Thus, after the connection is made you will just use the familiar I/O commands from Chapter 11. This is one of the nice features of Java networking.

Testing programs without a network

For many reasons, you might not have a client machine, a server machine, and a network available to test your programs. You might be performing exercises in a classroom situation, or you could be writing programs that aren’t yet stable enough to put onto the network. The creators of the Internet Protocol were aware of this issue, and they created a special address called localhost to be the “local loopback” IP address for testing without a network. The generic way to produce this address in Java is:

InetAddress addr = InetAddress.getByName(null);

If you hand getByName( ) a null, it defaults to using the localhost. The InetAddress is what you use to refer to the particular machine, and you must produce this before you can go any further. You can’t manipulate the contents of an InetAddress (but you can print them out, as you’ll see in the next example). The only way you can create an InetAddress is through one of that class’s overloaded static member methods getByName( ) (which is what you’ll usually use), getAllByName( ), or getLocalHost( ).

You can also produce the local loopback address by handing it the string localhost:

InetAddress.getByName("localhost");

(assuming “localhost” is configured in your machine’s “hosts” table), or by using its dotted quad form to name the reserved IP number for the loopback:

InetAddress.getByName("127.0.0.1");

All three forms produce the same result.

Port: a unique place

within the machine

An IP address isn’t enough to identify a unique server, since many servers can exist on one machine. Each IP machine also contains ports, and when you’re setting up a client or a server you must choose a port where both client and server agree to connect; if you’re meeting someone, the IP address is the neighborhood and the port is the bar.

The port is not a physical location in a machine, but a software abstraction (mainly for bookkeeping purposes). The client program knows how to connect to the machine via its IP address, but how does it connect to a desired service (potentially one of many on that machine)? That’s where the port numbers come in as a second level of addressing. The idea is that if you ask for a particular port, you’re requesting the service that’s associated with the port number. The time of day is a simple example of a service. Typically, each service is associated with a unique port number on a given server machine. It’s up to the client to know ahead of time which port number the desired service is running on.

The system services reserve the use of ports 1 through 1024, so you shouldn’t use those or any other port that you know to be in use. The first choice for examples in this book will be port 8080 (in memory of the venerable old 8-bit Intel 8080 chip in my first computer, a CP/M machine).

|

苏公网安备 32061202001004号

苏公网安备 32061202001004号